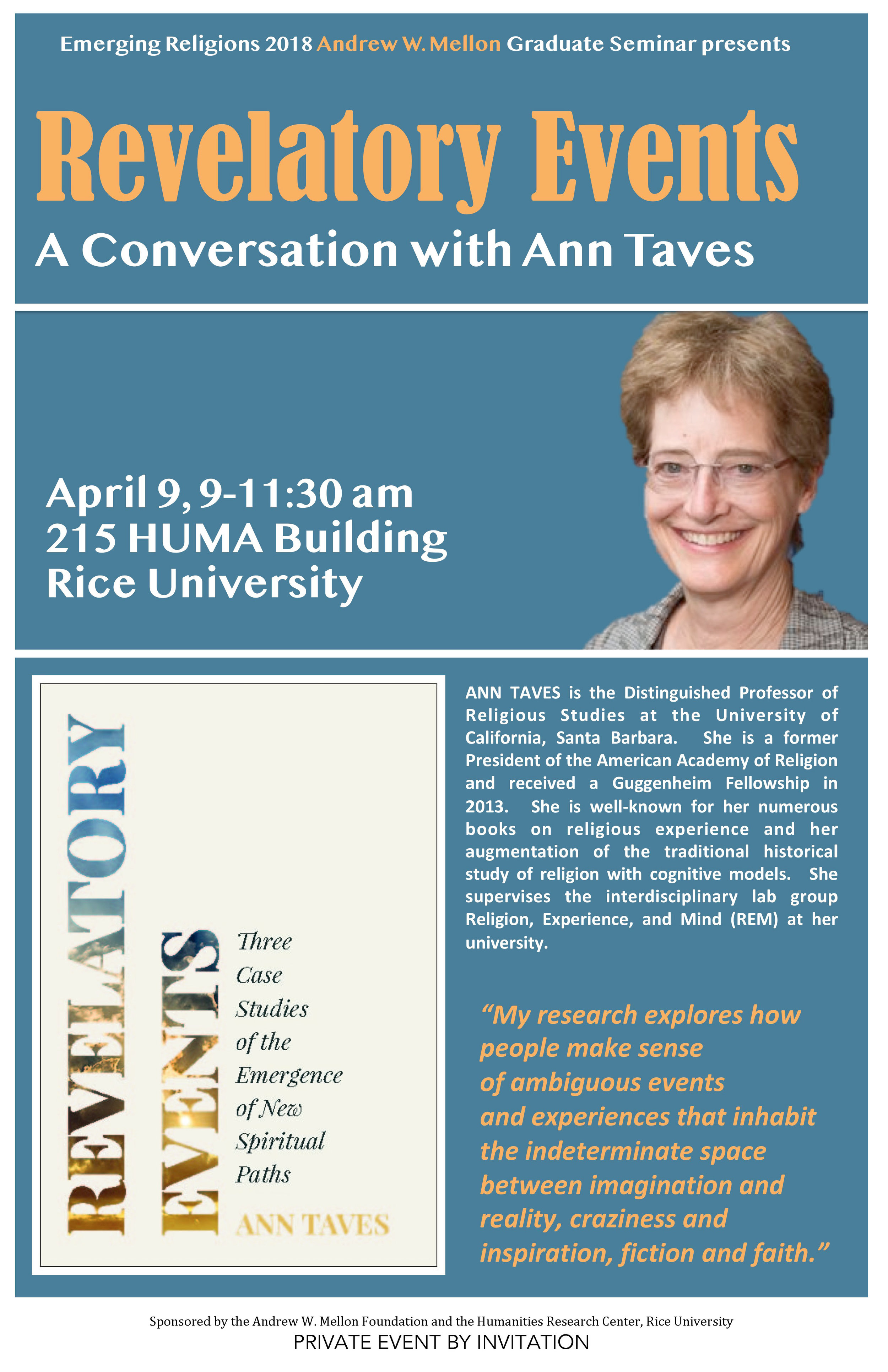

Ann Taves' Visit

/We had the pleasure of hosting Ann Taves' in our Mellon Seminar this morning. We had an inspiring discussion about the naturalness of extraordinary experiences and how they become religious experiences. She encouraged us to think of experiences as "events" that have shared evolved cognitive processes, cultural contexts (set and setting), and appraisals (interpretations we give the event). We discussed my concept of cognitive ratcheting and how this supports her idea that we share cultural schema that have become automatic for us. In other words, these culturally loaded frames are unconscious enough that they already structure the revelatory event while it is happening, and likely precondition the event too.

She shared her idea that we as humans have the capacities to make things seem real, and that some humans are able to cross over from the imaginary to the real with very little trouble. In her view, states like dissociation and hypnotic states have an innate component which can be trained and legitimated via its cultural value. She thinks of cognitive states that are dissociative or unitive to represent a more primal level of consciousness that usually in our daily activities is suppressed by the higher order of consciousness with its executive functions. We share this more dissociative state of the self with other animals. She believes that more work needs to be done thinking about the brain's default mode network, which is the operations of our brain when we are not doing a task, when we are not involved with the executive functions of the self.