"I didn't find a sublime Judas. I found a Judas more demonic than any Judas I know in any other piece of early Christian literature." -April DeConick

New York Times Op. Ed. on the Gospel of JudasApril DeConick writes that mistakes were made in the initial translation and interpretation of the Gospel of Judas

Gospel Truth published 12-1-07

Chronicle of Higher EducationAuthor Tom Bartlett follows the story of the Gospel of Judas and the Codex Judas CongressThe Betrayal of Judas: Did a "dream team" of scholars mislead millions?

Publication of The Thirteenth Apostle: What the Gospel of Judas Really Says (see sidebar)

- In 2006, National Geographic released the first English translation of the Gospel of Judas, a second-century text discovered in Egypt in the 1970s. The translation caused a sensation because it seemed to overturn the popular image of Judas the betrayer and instead presented a benevolent Judas who was a friend of Jesus.

- Writers and academics have been quick to seize the opportunity to "rehabilitate" Judas as to re-examine our assumptions about this archetypal figure.

- In The Thirteenth Apostle April DeConick offers a new translation of the Gospel of Judas which seriously challenges the National Geographic interpretation of a good Judas.

- DeConick contends that the Gospel of Judas is not about a "good" Judas, or even a "poor old" Judas. It is a gospel parody about a "demon" Judas written by a particular group of Gnostic Christians, the Sethians. Whilst many other leading scholars have toed the National Geographic line, Professor DeConick is the first leading scholar to challenge this "official" version. In doing so, she is sure to inspire the fresh debate around this most infamous of biblical figures.

An Interview with April DeConick about the Gospel of Judas

Can you tell me about the background of the Gospel of Judas? When does it date from, where was it found?

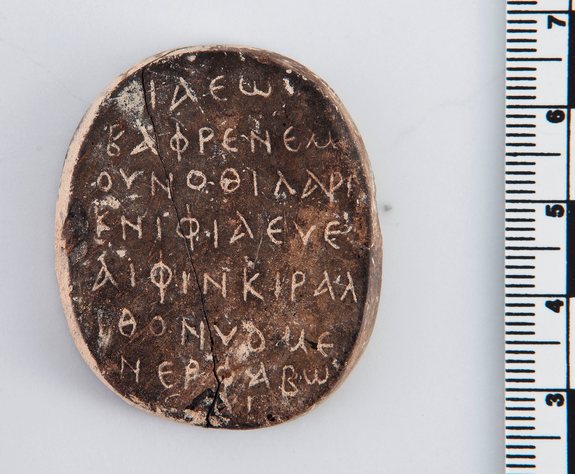

The manuscript was discovered in the 1970s in an ancient catacomb that was being looted by local peasants living near the cliffs of the Jebel Qarara. The Jebel Qarara hills are only a few minutes on foot from the Nile River not far from El Minya, Egypt. Although we know that the Gospel of Judas existed in the middle of the second century because Bishop Irenaeus of Lyons mentions it (ca. 180), the manuscript that we have is a fourth- or fifth-century Coptic translation. It was only one text in a book of Gnostic Christian writings.

It was buried along with three other books that had been copied in the fourth- or fifth centuries a book of Paul's letters in Coptic, the book of Exodus in Greek, and a mathematical treatise in Greek. All four books had been sealed in a white limestone box and buried in a family tomb. If nothing else, their burial in this tomb points to their favoritism in the life of an early Christian living in ancient Egypt, a Christian who seems to have had esoteric leanings, and no difficulty studying canonical favorites alongside the Gnostic Gospel of Judas. In fact, he appears to have wanted to take them with him in death.

Why did it take so long to make the first English translation?

The English translation wasn't what took so long. What took the time was recovering the text from the antiquities market, which finally was done in the early 2000s.It also took time to restore the manuscript so that it could be read. The book that contains the Gospel of Judas was in the worst possible shape due to terrible handling once it left the grave. It had been torn in parts to make quicker and more profitable sales. The pages had been reshuffled so that the original pagination was gone. It was brittle and crumbling thanks to a stay in someone's freezer. The ink was barely legible because of exposure to the elements. Members of the National Geographic team have told me that initially they photocopied every fragment and then used the photocopies to piece together the pages. They worked with tweezers to fit together the scraps of papyrus and also relied on state-of-the-art computer technology.

Once the restoration was complete, the manuscript could be read. It is written in an old Egyptian language called Coptic. The Coptic text had to be transcribed, which was no small job given the fragmented nature of the restored pages and the eroded ink. After the initial transcription was made, it was then translated into English.

What was it about the National Geographic translation that inspired you to make your own translation?

When National Geographic finally released the transcription and translation of the Gospel of Judas, I was enthusiastic because my area of expertise is ancient Gnostic religiosity and early Christian mysticism. Most of my career as a professor has been devoted to the study of the Nag Hammadi texts.

The Gospel of Judas came upon most of us out of a whirlwind. I had heard whispers about the Gospel of Judas for years, but nothing really concrete. Then there it was captured on film and on the web. I was repelled by the sensationalism of its release, but still attracted to the idea that here was a brand new Gnostic text that no one has read for how many centuries?! I guess I wanted to know what stories it had to tell us about the Christians who wrote it in the second century. And once I started to work out my own translation, I realized that I had an obligation to other scholars and to the public to set the record straight about what the Gospel of Judas actually says.

What makes your interpretation so different from the National Geographic version?

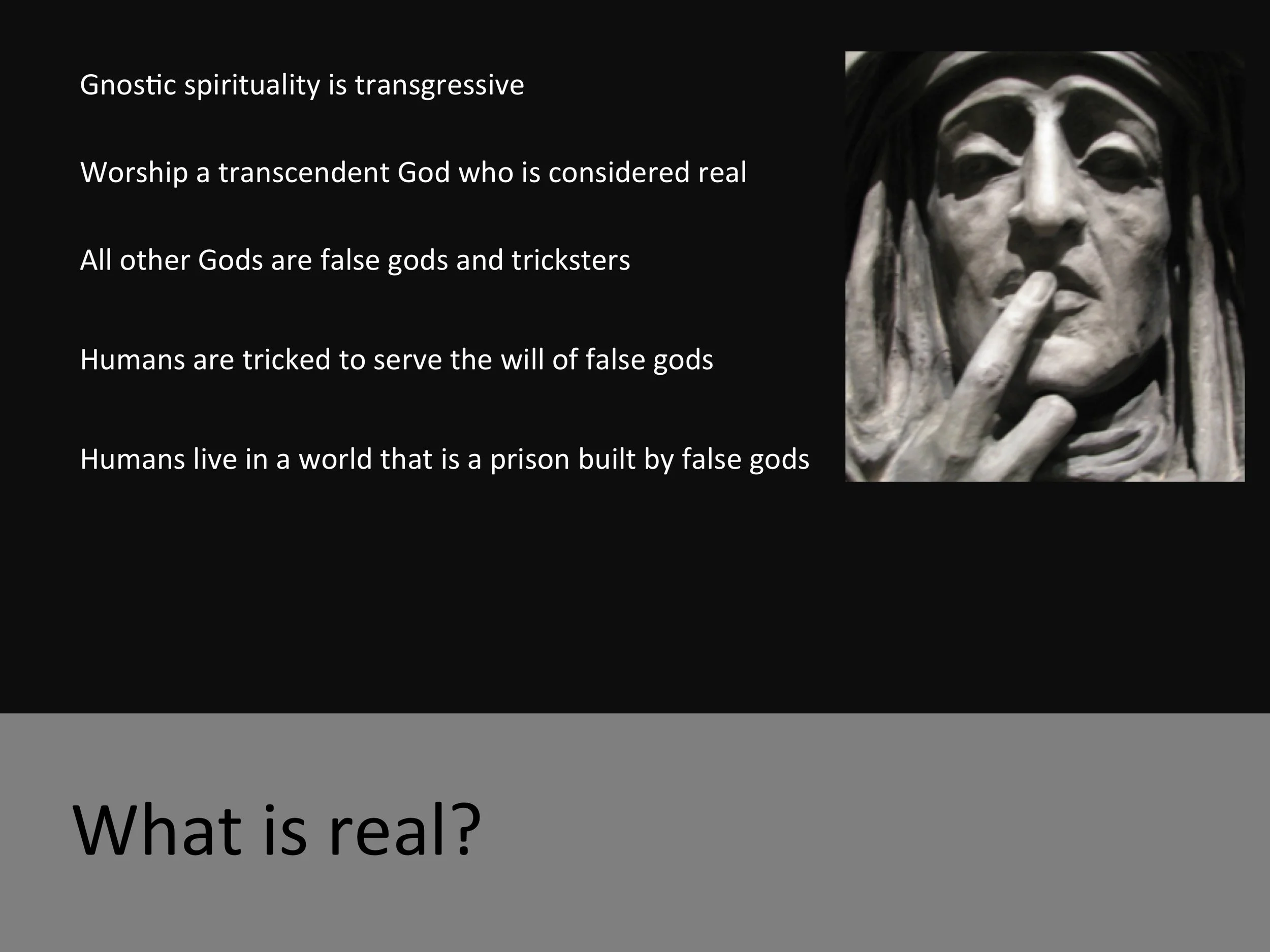

For a long time, scholars have thought that the Gospel of Judas featured a Judas hero because testimony from a couple of Church Fathers led us to believe that there were a group of Gnostics known as Cainites. The Cainites were said to believe that all the bad characters in the bible, including Judas, were actually heroes. I tend to be extremely skeptical of the testimony of the Church Fathers on these sorts of issues for the sheer fact that the Fathers saw the Gnostics as their opponents and they did everything they could to undermine them, including lying. So I didn't have an opinion on what the Gospel of Judas should say about Judas.

Once I started translating the Gospel of Judas and began to see the types of translation choices that the National Geographic team had made, I was startled and concerned. The text very clearly called Judas a demon. Why did the team feel it necessary to translate this "spirit"? The text very clearly says that Judas will be "separated from" the Gnostics. Why did the team feel it necessary to translate this "set apart for" the Gnostics? And so forth.

I didn't care if Judas was good, bad or ugly. I just wanted to hear what the Sethian Gnostics had to say about him, and make sense of the text as a whole.

Why do you think that the National Geographic interpretation doesn't work?

Not only is this interpretation based on a problematic English translation, rather than on what the Coptic actually says, but the opinion that Judas is a hero and a good guy is nonsense in terms of the bigger gospel narrative. For instance, this gospel berates sacrifice and understands it to be a horrifying practice dedicated to the god who wars against the supreme Father God. If this is the case, then Judas' sacrifice of Jesus simply cannot be a good thing. To say it is, is to rip apart the logic of what the text is saying as a whole.

Why do think so many scholars and writers have been inspired by the National Geographic version?

I have been truly amazed at the number of people who have jumped on this bandwagon. One of my colleagues upon hearing my concerns at a conference, stood up and said, "I just don't see why Judas can't be good. We need a good Judas." This really stopped me in my tracks and took this discourse to an entirely new level for me.

There is something bigger going on here, in our modern communal psyche. I haven't been able to put my finger on it exactly, but it appears to have something to do with our collective guilt about anti-Semitism and our need to reform the relationship between Jews and Christians following World War II.

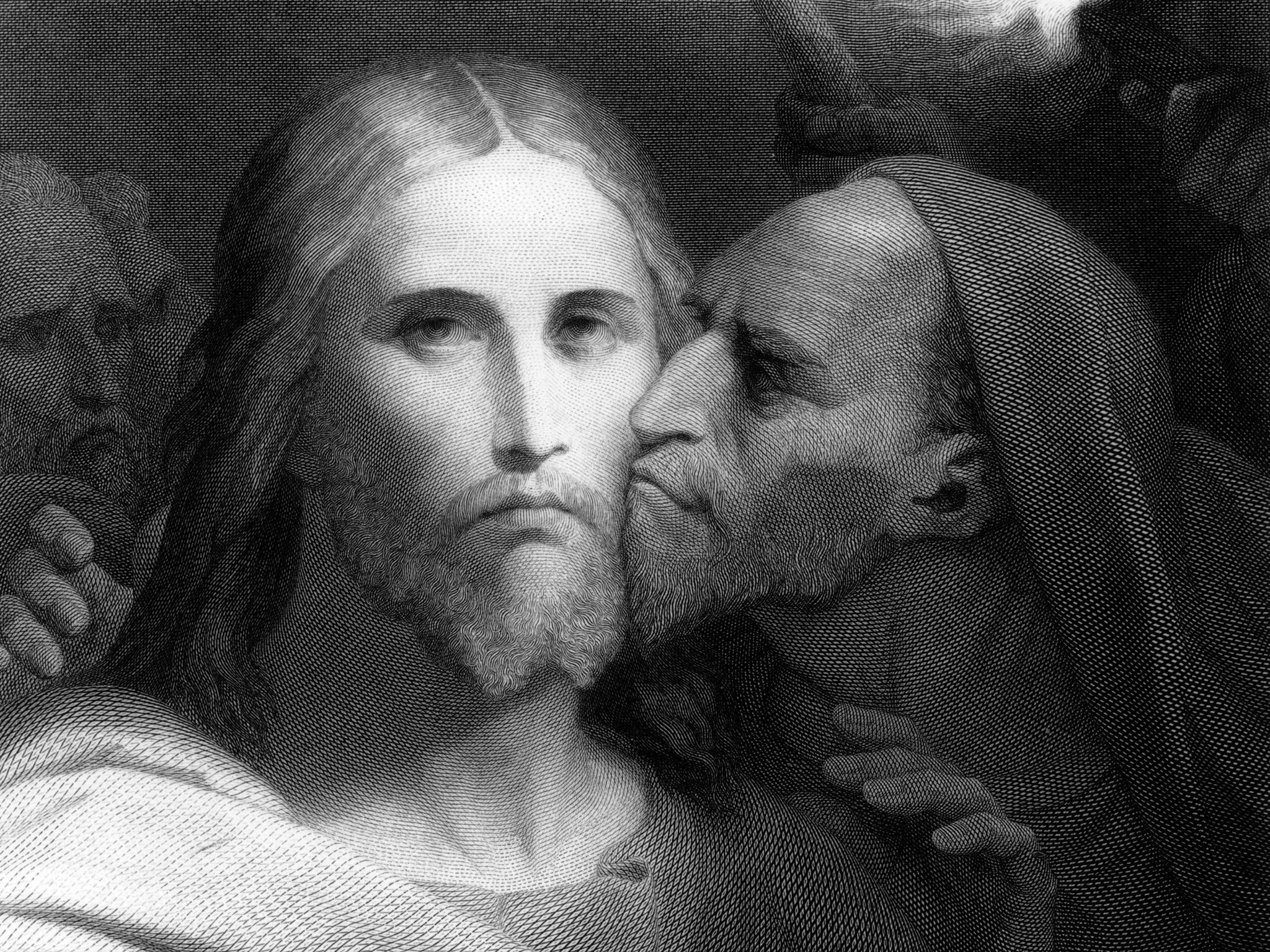

Judas has been a terrifying figure in our history, since he became in the Middle Ages the archetypal Jew who was responsible for Jesus' death. His story was abused for centuries as a justification to commit atrocities against Jews. I wonder if one of the ways that our communal psyche has handled this in recent decades is to try to erase or explain the evil Judas, to remove from him the guilt of Jesus' death. There are many examples of this in pop fiction and film produced after World War II. It seems to be that the National Geographic interpretation has grown out of this collective need and has been well-received because of it.

Who do you think wrote the Gospel? Why do you think they wrote it?

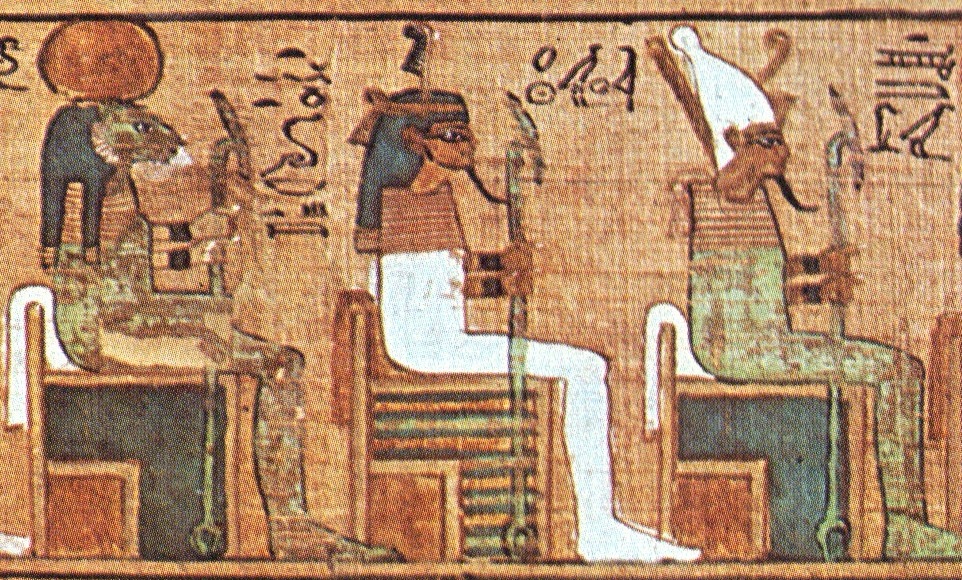

The Gospel of Judas was written by Gnostic Christians called Sethians in the mid-second century. They wrote it to criticize Apostolic or mainstream Christianity, which they understood to be a form of Christianity that needed to reassess its faith. Particularly troubling for these Gnostic Christians was the Apostolic belief in the atonement, because this meant that God would have had to commit infanticide by sacrificing the Son. They wrote the Gospel of Judas to prove that this could not be the case. Why? Because Judas was a demon who worked for another demon who rules this world and whose name is Ialdabaoth. How did they know this? Because Jesus had revealed this to Judas before Judas betrayed him. That is the bottom line. That is what this gospel says.

What do you think this manuscript tells us about early Christianity? Why is the Gospel of Judas important?

This gospel's voice is different. It represents the opinions of Christians in the second century who came to be labeled as "heretical" by later bishops who wished to gain control of the religious landscape. Because this is a Gnostic Christian tradition that did not survive, the chance find of this gospel has let us tune into a second century discussion about theology. And the voice we are hearing is the voice of the guy who lost the debate.

Not only is the recovery and integration of this voice into our history important, but also its contribution to Christian theology, which is enormous. The challenge against atonement theology as it is presented in the Gospel of Judas is a challenge that rocked the Apostolic Churches, forcing them to refine and recreate their position. The end result is a doctrine of atonement that became very popular in the Christian Church, a doctrine that understood the sacrifice of Jesus as a ransom paid to the Devil. This doctrine exists as a response to the Gnostic criticisms of atonement that we find in the Gospel of Judas.

What do you think it is about the figure of Judas that seems to fascinate both scholars and the general reader?

Judas Iscariot is a frightening figure. For Christians, he is the one who had it all, and yet betrayed God to his death for a few dollars. He is the archetype of human evil, the worst human being ever to live. He is the antithesis of the true Christian. Because of this, his image works as a religious control - he is someone the Christian never wants to become. For Jews, he is terrifying, the man whom Christians associated with Jewish people, whose story was used against them for centuries as a religious justification for their abuse and slaughter. Even his name "Judas" has been linked to "Jew," due to their root similarities (Judas/Judea/Jews). I think that Judas is someone whose shadow haunts us.

Reading on the Gospel of Judas

Andrew Cockburn, May 2006. "The Judas Gospel." Pages 78-95 in

National Geographic Magazine.

This is National Geographic's story of the year, perhaps of the century. Mr. Cockburn, a National Geographic author, writes an overview of the discovery and restoration of the Gospel of Judas in fine journalistic style. Beautiful photographs by Kenneth Garrett grace the pages. 17 pages.

Bart D. Ehrman, 2006.

The Lost Gospel of Judas Iscariot: A New Look at Betrayer and Betrayed (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

Professor Ehrman discusses his own involvement in National Geographic's project to analyze the Gospel of Judas along with the tale of the discovery of Judas. He describes the contents of the gospel, its relationship to the New Testament gospels, suggesting that it presents a unique view of Jesus, the twelve disciples, and Judas who is the only one who remains faithful to Jesus even to his death. 198 pages.

Rodolphe Kasser, Marvin Meyer, and Gregor Wurst, with additional commentary by Bart D. Ehrman, 2006.

The Gospel of Judas (Washington D.C.; National Geographic).

The original publication of the English translation of the Gospel of Judas made by Professors Rodolphe Kasser, Marvin Meyer, and Gregor Wurst, in collaboration with François Gaudard. It includes chapters of commentary on the story of the Tchacos Codex (by Kasser), Judas as a typical Gnostic text and alternative vision of Judas (by Ehrman), early mentions of the Gospel of Judas by the Church Fathers (by Wurst), and Judas as a Sethian gospel (by Meyer). 185 pages.

Herbert Krosney, 2006.

The Lost Gospel of Judas: The Quest for the Gospel of Judas Iscariot (Washington D.C.: National Geographic).

Herbert Krosney is an investigative journalist who traces in his book what can be known about the discovery, recovery, and restoration of the Gospel of Judas. Includes a brief foreword by Bart Ehrman and an epilogue by Marvin Meyer. 309 pages.

Nicholas Perrin, 2006.

The Judas Gospel (Downers Grove: Intervarsity Press).

Nicholas Perrin provides us with a brief history of the discovery of the Gospel of Judas in this pamphlet. He makes an overview of the contents as a second century Gnostic gospel. He argues that the text has little historical value in terms of telling us anything about Jesus and Judas. Rather its value comes from what it reveals about gnostic alternatives to what Perrin understands as "authentic" Christianity. 32 pages.

James Robinson, 2006.

The Secrets of Judas: The Story of the Misunderstood Disciple and his Lost Gospel (San Francisco: Harper).

Professor James Robinson discusses what can be known about the historical Judas from the Bible and other ancient Christian texts. He recounts the story of the discovery of the Gospel of Judas and its sensationalistic release by National Geographic, criticizing the way in which the publication of the text has been handled. 192 pages.

N. T. Wright, 2006.

Judas and the Gospel of Jesus: Have We Missed the Truth about Christianity? (Grand Rapids: Baker Books).

Bishop Wright argues that the Gospel of Judas tells us nothing about the historical Jesus or the historical Judas. Its rehabilitation of Judas in this second century text cannot be linked to the real Judas who betrayed Jesus. He thinks that the publication of this gospel is part of a scholarly agenda to find an alternative Jesus, which has another sensationalistic life in popular literature like The Da Vinci Code - financial profit. 155 pages.

Elaine Pagels and Karen L. King, 2007.

Reading Judas: The Gospel of Judas and the Shaping of Christianity (New York: Viking).

This book contains Karen King's own English translation of the Gospel of Judas, followed by a brief running commentary. The other chapters are written collaboratively by Professors Pagels and King. These chapters attempt to contextualize Judas within the milieu of early Christian persecution and martyrdom, suggesting that the Christians who wrote this gospel were condemning church leaders who were encouraging their flock to die as sacrifices to God. 198 pages.

Craig A. Evans, 2006.

Fabricating Jesus: How Modern Scholars Distort the Gospels (Downers Grove: Intervarsity Press).

Included in the back of this book is a brief appendix, "What Should We Think About the Gospel of Judas?" He mentions his own involvement on the National Geographic team and the text's recovery. He outlines the contents of the Tchacos Codex yet to be published. This is followed by a short description of the contents of the gospel and its meaning, weighing in on the perspective of the Church Fathers - that the gospel honored Judas because it was written by a Gnostic who revered all the "evil" men in the scriptures. These villains like Judas were only "evil" in the eyes of Yahweh the lesser god because they worked for the God of light in his war against Yahweh. So in reality, the villains were the good guys. 6 pages.

Favorite Posts about the Gospel of Judas